George Mink Jr. is a health care outreach worker in Delaware County, Pa. He worries about what will happen when vaccines are no longer paid for by the federal government. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

hide caption

toggle caption

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

George Mink Jr. is a health care outreach worker in Delaware County, Pa. He worries about what will happen when vaccines are no longer paid for by the federal government. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

Robert, who lives in Philadelphia, knows signing up for Medicaid can be tricky with his ADHD, so he brought his daughter along to help him fill out the paperwork.

“If we miss one little detail, they would reject you,” says Robert, who has had the government health insurance for people on low incomes in the past. “I usually get two applications, so if I mess up on one. I can do the other one.”

This time, with his daughter’s help, the application only took Robert a half hour. (NPR agreed to use Robert’s first name only because he has a medical condition he would like to keep private.)

Signing up for Medicaid correctly is about to become an important step for enrollees again after a three-year break from paperwork hurdles. In 2020, the federal government recognized that a pandemic would be a bad time for people to lose access to medical care, so it required states to keep people on Medicaid as long as the country was in a public health emergency. The pandemic continues and so has the public health emergency, most recently renewed on Jan. 11.

But the special Medicaid measure known as “continuous enrollment” will end on March 31, 2023 no matter what. It was part of the budget bill Congress passed in Dec. 2022. Even if the public health emergency is renewed in April, states will begin to make people on Medicaid sign up again to renew their coverage. And that means between 5 and 14 million Americans could lose their Medicaid coverage, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, the nonpartisan health policy organization..

The federal Department of Health and Human Services expects 6.8 million people to lose their coverage even though they are still eligible, based on historical trends looking at paperwork and other administrative hurdles. Pre-pandemic, some states made signing up for and re-enrolling in Medicaid very difficult to keep people off the rolls.

In the three pandemic years, the number of Americans on Medicaid and CHIP – the Children’s Health Insurance Program – swelled to 90.9 million, an increase of almost 20 million.

Jenn Lydic is the director of social services and community engagement at the Public Health Management Corporation, a nonprofit that runs six health centers in Philadelphia. She says the reprieve from renewal paperwork “allowed for a continuity that I think has really been lifesaving for a lot of folks.”

“I know so many patients who have now been able to really finally get ahead of a lot of their health conditions,” Lydic says.

Research shows that disruptions in Medicaid coverage can lead to delayed care, less preventative care, and higher health care costs associated with not managing chronic conditions like diabetes and substance-use disorder.

Philadelphia Health Commissioner Cheryl Bettigole worked in city health centers for years. She said the continuous Medicaid enrollment and pandemic measures like free access to COVID-19 tests and treatments have been a big advance. She would like to see some of that last.

“There was this moment with the pandemic in which we recognized that it was really important for everybody to have access to care. And we’ve somehow changed our minds about that,” says Bettigole. “If we were to have a newer, better vaccine that lasts longer, we would want everyone to get that. We recognized it for a moment, for a single condition, and now we’re kind of walking back from that. I do think that’s a pity.”

The boosted Medicaid rolls mean the country has a historically high rate of people with insurance at 92{fc1509ea675b3874d16a3203a98b9a1bd8da61315181db431b4a7ea1394b614e}. That rate is likely to erode as Medicaid winnows down again. States do have some discretion on how they re-start the sign up process. It could take a few months to a year. If a state finds someone to be no longer eligible for Medicaid, they won’t be cut off immediately, said Jennifer Tolbert, associate director for the program on Medicaid and the uninsured at the Kaiser Family Foundation. The Pennsylvania Department of Human Services said it will take a full year to do this and is working to make sure no one experiences a lapse in health coverage.

The federal government also increased Medicaid funding to the states in 2020, and that increased funding won’t start phasing out until the end of 2023. Tolbert added that the move to keep people enrolled on Medicaid continuously is truly unprecedented, but there will be some lasting changes from the pandemic.

For instance, Oregon will allow children who qualify for Medicaid to enroll at birth, and stay enrolled until age 6, without having to reapply. Washington, California, and New Mexico are considering similar policies as well.

Another concern is what happens when the federally-funded supply of COVID-19 vaccines and tests ends. Last August, the federal government announced they do not have more funds from Congress to pay for COVID-19 vaccines. In March 2022, the federal government stopped paying for tests for uninsured patients.

George Mink Jr. is a community activist for Health Educated, a nonprofit in Delaware County that has hosted vaccine clinics, health fairs, and webinars. He took advantage of free Covid testing and vaccines early in the pandemic. Mink said he might not have gotten tested if he had to have health insurance or pay for it himself. He has not had any serious health issues, but in 2020, a close family friend died from COVID-19. Mink and his family got tested and found out they were positive.

“Who knows what could have happened?’ he says. “We still would have been … infecting other people. It made a major difference.”

Mink is also up to date with his COVID-19 vaccinations, but worries about what will happen when the vaccines are no longer free: “What if in two months, we got a new variant coming and now I need a new booster, and now I can’t afford it?”

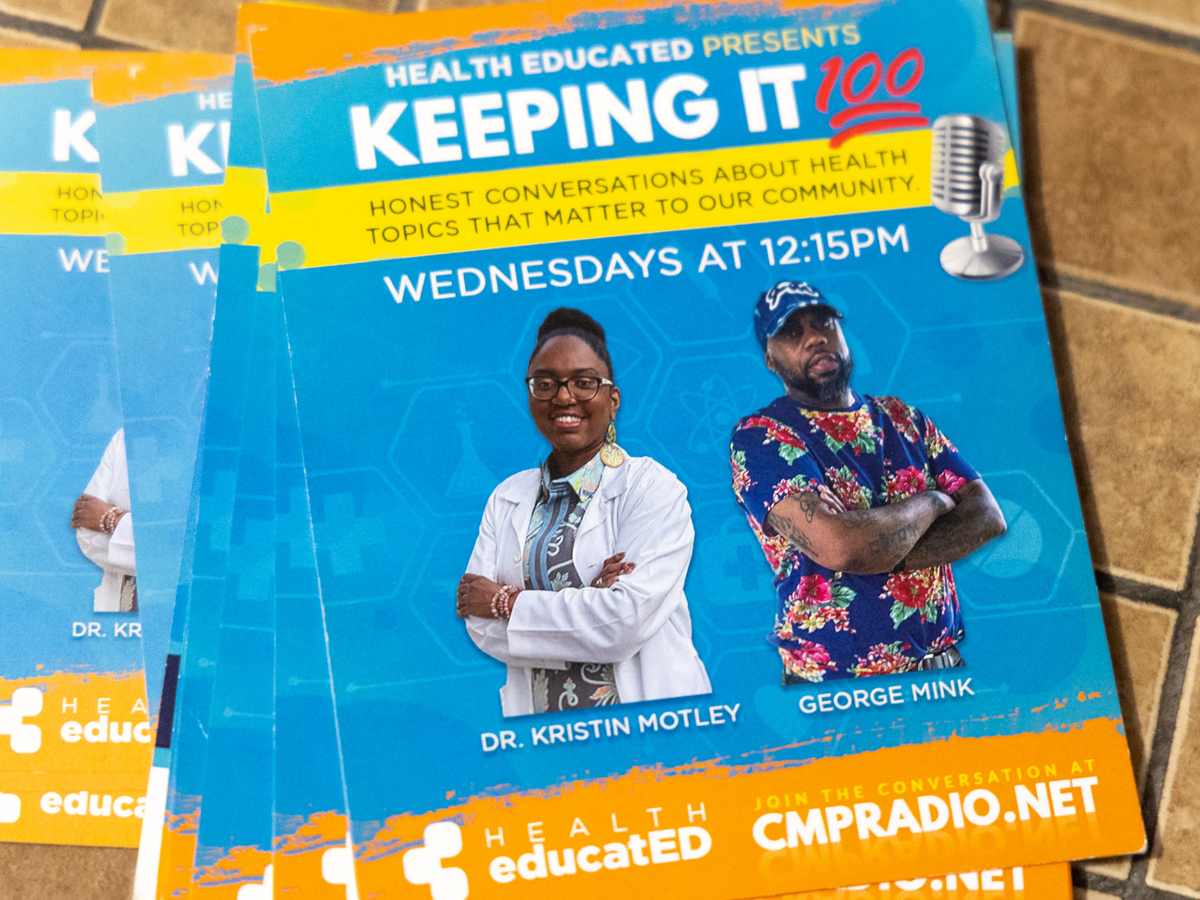

Dr. Kristin Motley, a pharmacist, founded Health Educated, an outreach organization in Delaware County, Pa. Flyers for the podcast she hosts with George Mink Jr. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

hide caption

toggle caption

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

Dr. Kristin Motley, a pharmacist, founded Health Educated, an outreach organization in Delaware County, Pa. Flyers for the podcast she hosts with George Mink Jr. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

The health departments in Pennsylvania and Delaware say they plan to keep providing free tests and vaccines for the foreseeable future, and that the federal government has yet to say when the free vaccine supply will be cut off.

Pharmacist Kristin Motley, the founder of the Health Educated nonprofit where Mink works, will be sorry to see the free vaccines go.

“It allowed us to go into the community, wherever people were and to say, you don’t have to register, you don’t have to bring I.D., you don’t have to bring insurance. You just come,” she says. “That was really nice to be able to help people in that way with no red tape, no bureaucracy. It was so seamless.”