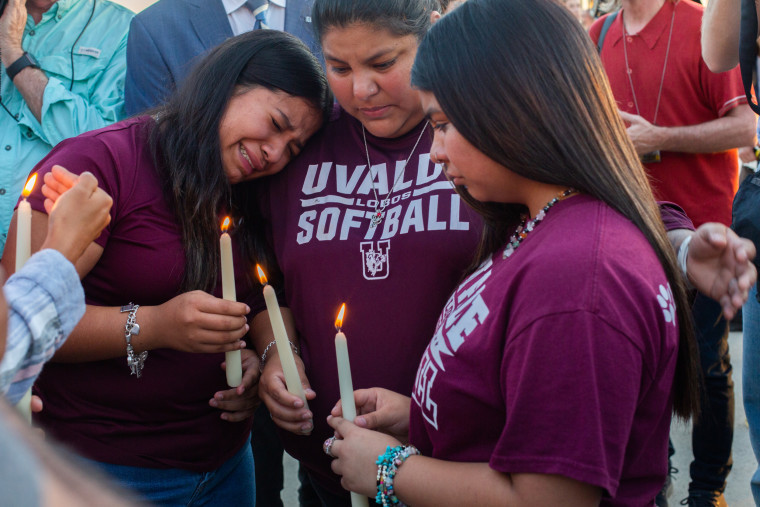

UVALDE, Texas — In a picture that Mehle Taylor, 10, drew of Rogelio Torres, one of her close friends brutally killed in last month’s school shooting massacre, he wears his favorite red-and-black jacket.

Mehle told her mother how much she misses the boy, who had been her “bus buddy” since pre-kindergarten.

“How do I even begin to tell her she’s never going to see her friend Rogelio again on the bus?” her mother, Tina Ann Quintanilla-Taylor, told NBC News.

Quintanilla-Taylor has not yet sought mental health counseling for Mehle, even though she fears she could later experience post-traumatic stress syndrome or fear returning to school. For now, she’s kept her daughter from watching the news and attending memorials or funerals. She decided to let Mehle cope in her own way, at her own pace.

Days after the May 24 shooting, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott promised an “abundance of mental health services” to help “anyone in the community who needs it … the totality of anyone who lives in this community.” He said the services would be free. “We just want you to ask for them,” he said, before giving out the 24/7 hotline number — 888-690-0799.

That’s a tall order for a community in an area with a shortage of mental health resources, in a state that ranks last for overall access to mental health care, according to a 2022 State of Mental Health in America report.

Mental health organizations are assembling a collection of services to assist those who seek help in Uvalde. But there have been hiccups and hitches along the way.

There is worry that what’s being offered is not coming together as fast or efficiently as it could be, and that it’s being assembled without keeping in mind the community it serves: Many residents are lower income, and some may have difficulties with transportation, or are mainly Hispanic. Many are not accustomed to seeking out therapy, or are distrustful of who is providing it.

Quintanilla-Taylor didn’t believe many would use the mental health services and had doubts about their long term availability.

“It’s not going be prevalent. … I don’t trust the resources, and that’s coming from an educated person,” said Quintanilla-Taylor, who’s pursuing a doctorate in philosophy and specializing in organizational leadership at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Haunted by ringing phones

Eulalio “Lalo” Diaz said he still hears the rings of phones from the backpacks of the slain children in Room 112 and from the desk phone of Irma Garcia, their teacher who had tried to protect them.

By then, parents and families were calling “with the hopes that their children would answer. Knowing they wouldn’t, that hit me very hard,” said Diaz, the Uvalde County justice of the peace who was on duty when a gunman slipped through a back door of Robb Elementary School with a high-powered rifle and began firing.

The job of identifying the dead and informing parents fell to Diaz.

Days after the shooting, Diaz’s cousin and Uvalde native Monica Muñoz Martinez learned that Diaz and some families had not been contacted about counseling. She began the work of lining it up, taking up Abbott on his promise by calling the Uvalde Mental Health Support Line, the 24/7 hotline.

But when Martinez called the mental health hotline to seek services that Memorial Day weekend, she faced a frustrating, time-consuming process. Diaz was added to a list of first responders who might need counseling after Martinez’s calls.

“It was not helpful for me,” Martinez said. The historian, author and University of Texas at Austin professor said she was bounced around multiple phone lines and given conflicting information about walk-in counseling services.

When she was told to call a therapist for care, Martinez asked for a list of recommended therapists. She was told to call her insurance company and warned that she “would have to pay for individual counseling,” even though the governor had touted free services.

Diaz has met virtually with a therapist based in Austin since then. He said it’s helped to talk to someone not connected to the community. His family, too, has been provided support, he said.

While there was “chaos” at the beginning, Diaz said there now seemed to be progress in getting help in place for people who seek it. He believes it’s a mistake to put the resiliency center in a building off Main Street, which may not offer enough privacy for some people.

“I don’t think the response was here early on proactively. They were here, but you almost had to make an appointment and show up. … It’s not go knocking on doors and finding people saying, ‘Look, I’m checking on your son, or I’m checking on your daughter, or I’m checking on y’all. How are y’all doing?’

“People aren’t just going to show up,” Diaz said. “I know parents who have kids that were at Robb who were two or three rooms down or were teachers and they still haven’t taken their kids yet.”

‘We need to get better’

Uvalde County Commissioners, the countywide government body, voted Thursday to purchase a building to create the Uvalde Together Resiliency Center to to serve as a hub for long-term services, such as crisis counseling and behavioral health care for survivors.

Abbott set aside $5 million in funding for the center, which has been operating at the county fairgrounds.

Texas Sen. Rolando Gutierrez, whose vast district includes Uvalde, said the community needs continuity of care and rather than create a new building the state could invest in the existing local community health clinic, in operation for 40 years and already serving 11,000 uninsured Uvalde residents.

“These are people who have behavioral health on the ground. They actually have the one psychiatrist in Uvalde right here,” Gutierrez said Friday referring to the clinic. “We needed to have the budget so that we can bring in therapists, which we would have been able to do with that money. Instead, they’re starting from whole cloth this promised center you’re going to have the district attorney run?”

Gutierrez, who has shifted a district office from Eagle Pass to Uvalde, said he met with 11 families whose children survived the shootings and were either wounded or sent to the hospital.

“What the families have been telling me is they don’t want to see one therapist one week, a different one the following and another one yet maybe the next week,” he said. “So, they are having trouble with appointments, with continuity and that’s very, very important, especially when we are talking about young children.”

Gutierrez said he sent a letter to Abbott asking for $2 million for the existing free community clinic to provide crisis care but has not heard back.

In Uvalde, almost 1 in 4 residents are uninsured. Uvalde is roughly 80 percent Hispanic, with most of that share having Mexican roots.

At the meeting with the families, several said they didn’t have any “significant contact” with the district attorney’s office, which is overseeing the resiliency center. Families are running into other problems, such as missing pay from work. One had power cut off, he said. He said that is an area where “we need to get better.”

Community Health Development Inc., the community clinic, said it has already “cared for patients and eyewitnesses of the event” and promised to offer services to the community “at no cost.” It is also in “the process of securing federal and private resources to build our capacity for long-term care.”

Roughly two months before the Uvalde massacre, Abbott slashed $211 million from the state department that oversees mental health programs.

The mass shooting at Robb Elementary School has exacerbated the lack of mental health care in the tight-knit community, said Uvalde therapist Jaclyn Gonzalez, who has been reaching out to families to get them services.

“There’s not enough of us to go around,” Gonzalez said. “Everybody has something: anxiety, depression, panic disorder; just Covid alone created that.”

What’s on the ground

Counseling offered at the Uvalde County Fairplex immediately after the shooting was available from 9 a.m .to 5 p.m., during work hours, and no accommodation was made for people without cars, Martinez said. Diaz did not want to go to the Fairplex because he feared his presence would unsettle the family members of the victims.

The hours have since changed and the Fairplex is now operating from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. A therapist is available at El Progreso Memorial Library for walk-in requests at the local library during the hours the library is open during the week. For now, that includes Saturday.

As of June 1, the Hill Country Mental Health Center and the Harris Call Center had responded to 201 support calls to the Uvalde Mental Health Support Line, the Texas Health and Human Services stated in an email. The state agency said it contracted both centers to collaboratively operate the hotline.

Texas Health and Human Services said that apart from entities and providers who work directly with them, 39 other local mental health and behavioral health organizations are helping to “provide additional supports and relief” in Uvalde.

While not having health insurance can limit access to health care, community health centers such as Uvalde Behavioral Health, part of the South Texas Rural Health Services network, often “make all kinds of concessions if a patient does merit mental health” services, CEO Myrta Garcia previously told NBC News.

‘What we need now is a public education campaign’

Martinez recalled a woman working at a convenience store shortly after the shooting. “She looked shattered,” Martinez said.

When Martinez asked the woman if she was OK, the woman started to cry and pointed to a newspaper photo of one of the students who was killed.

“That’s my baby, that’s my nephew,” the woman said. But when Martinez asked her if she had received any counseling, the woman said, “That isn’t for me,” and said she hadn’t heard about the availability of free mental health services.

Martinez has been referring families to the professional counseling available through Sacred Heart Catholic Church, a parish attended by many of the families, where many of the funerals were held.

“What we need now is a public education campaign so people can understand when they need help,” Martinez said, who’s meeting with a fellow educator to discuss its formation. “Everyone is in crisis, not just people directly affected.”

Meanwhile, a joint committee of state lawmakers will be examining various issues around the shooting, including mental health.

Uvalde resident Amber Ybarra, a mental wellness coach, has been helping her family cope by “calling one person every day.” She’s been doing this with her mom — “she’s struggling right now” — who lives less than a mile away from Robb Elementary, which Ybarra and her brother attended as children.

Two of Ybarra’s first cousins who had children who were at the school at the time of the shooting have been able to receive ongoing therapy through the local resources, she said.

“That’s really helping them,” she said, adding this is the first time her relatives had sought this kind of help.

Ybarra and about 30 of her cousins have started a WhatsApp group to help one another navigate tensions and fallout from the massacre.

“We’re a tight-knit community, we can lean on each other, but don’t forget that your neighbor might also be (from) the safety department or police station that your other neighbor is trying to blame for not responding fast enough,” she said.

Gonzalez, the therapist who’s been reaching out to families, said language and cultural differences can be roadblocks for those who need care.

“If you’re bilingual or your native language is Spanish, then speaking in Spanish is important because it becomes healing. It’s connects directly to your soul,” Gonzalez said.

Tele-health services, Gonzalez said, can serve as a resource for predominantly Mexican American families with cultural norms that often compel them to keep personal matters private.

For now, Gonzalez relies on word of mouth to connect with families in need and offers her services at no cost. That’s how she could start to provide counseling to a father who lost a child in the shooting.

“They didn’t come to me,” Gonzalez said. “I’m finding them.”

Suzanne Gamboa reported from San Antonio and Uvalde, Texas, and Nicole Acevedo reported from New York.